TikTok’s algorithm must have the best PR in all of tech: a prevalent view is that it’s the singular magic behind TikTok’s success:

Total disagreement on my timeline right now as to whether the value of TikTok is 100 percent in its algorithm, or 100 percent in its user base. Where do you land? (I'm more and more convinced that it's the user base) [POLL]

— Casey Newton (@CaseyNewton) September 13, 2020

With the news that the TikTok/Oracle won’t include the algorithm and the possibility that Oracle will have to replace it, some have concluded that TikTok’s popularity will flatline, that it’s only a matter of time before Facebook eats their lunch via Instagram Reels. But despite Facebook’s previous success at cloning the competition, TikTok is a much more formidable challenge: they’ve built strong network effects on top of a unique graph that Facebook doesn’t have – one built on niche interests and esoterica rather than people you know or recognize. Historically, social products have been extremely durable to competition because of network effects, even more so when the graph is unique – Facebook being a prime example. Take the algorithm out of TikTok and it’ll certainly be hampered, but pure algorithmic advantages aren’t that strong of a moat: best practices dissipate through industry quickly, and most of what makes ML good in the first place is the underlying training data generated by user activity.

If network effects are what keeps TikTok on top today, is the algorithm responsible for getting TikTok here in the first place? The answer is a lot more complex than that.

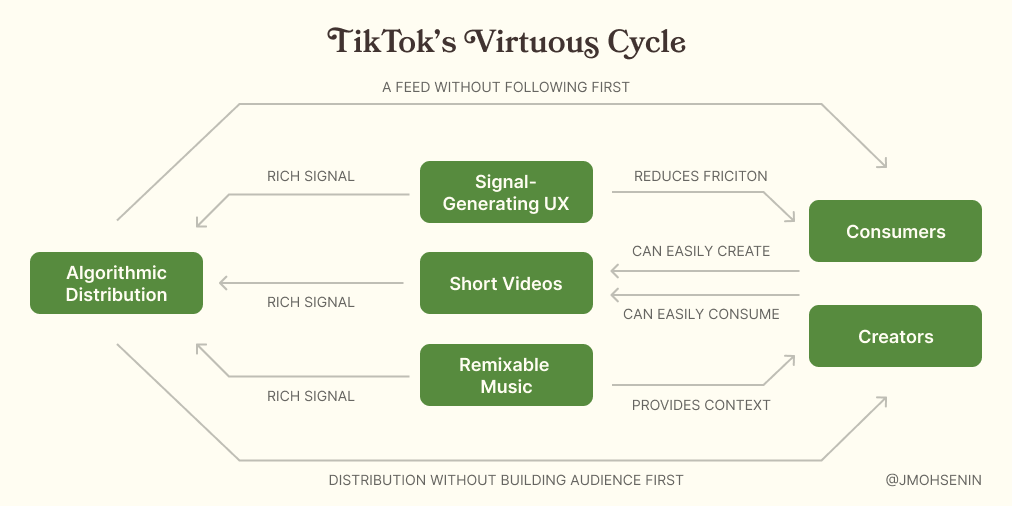

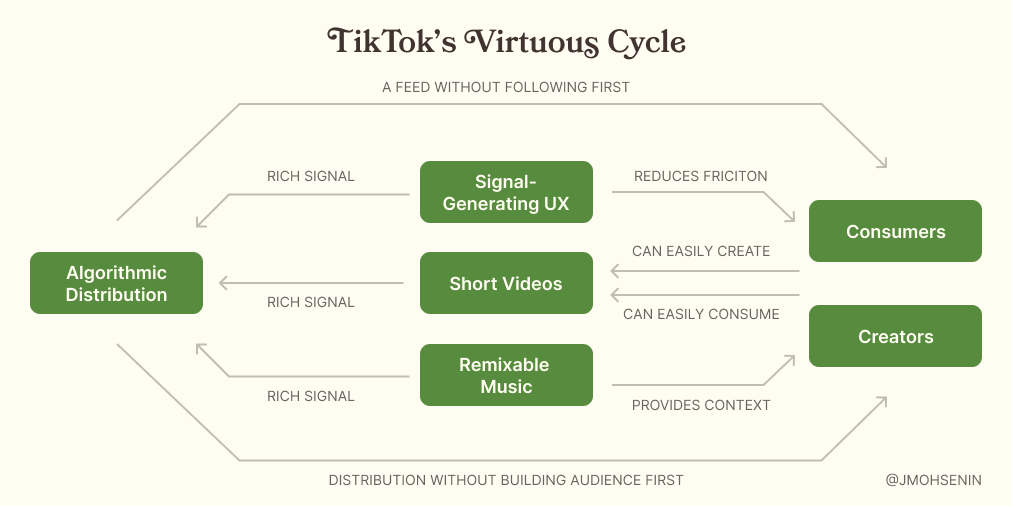

TikTok’s Virtuous Cycle

To understand TikTok’s strategy, Michael Porter’s framework is a useful guide. In his seminal “What Is Strategy?” paper (non-paywall slide summary), he laid out a framework for what defines a successful strategy:

- Strategy relies on unique activities: the essence of strategy is choosing to do different things and not just rely on general operational effectiveness, which is easily copyable.

- Strategic strength comes from the fit between unique activities: the unique activities need to be compatible, and ideally compound, such that the total value of all of them is larger than the sum of its parts.

- Activities must require tradeoffs: some activities are incompatible with each other, while others are a large opportunity cost. If neither is true about the activities a company chooses, a competitor can engage in those same activities with little downside.

When a strategy is successful, it often forms a virtuous cycle: the activities compound in a powerful feedback loop that causes the product to improve at a faster and faster rate. What is TikTok’s virtuous cycle? Understanding their core activities is a crucial first step:

- Videos are short, making them easy to consume and to make

- Consumers mostly watch videos made by creators they don’t know in real life (family/friends) or recognize (influencers/brands)

- Videos are primarily distributed by an algorithm instead of by a follow graph

- TikTok’s UX (auto-playing videos watched one at a time) generates rich signal for every video watched, helping the algorithm learn a person’s preferences quickly (to be expanded on in a future post)

- Music is remixable and the main way trends get started and grow

These activities aren’t all unique to TikTok – videos on Instagram are short, YouTube distributes videos algorithmically – but how they fit together and compound is unique to TikTok:

- ML algorithms like TikTok’s suffer from the cold start problem: it’s difficult to make good predictions about what you will like before you use it. The videos on TikTok are short, so it’s easy for consumers to watch many of them at once, and their UX provides rich signal about every video.

- If the videos are short, you need a lot of it to fill the 45 minutes per day the average person spends on TikTok. Making consumers follow enough creators to fill up a feed would be extremely cumbersome, so instead TikTok pulls in creators from everywhere in the main “For You” page. This is only possible because the algorithm can quickly learn about consumer’s preferences via the rich signal from short videos.

- How do creators know what kinds of videos to make, and how will the find an audience? Remixable music provides a signal of demand about what consumers want to watch and provides context and an audience for a creator to riff off of, no matter how weird.

The compounding strength of this strategy is made crystal clear when you consider how frictionless it is for both creators and consumers to have a great experience on TikTok, and how it gets better for both groups as TikTok gets bigger:

- Creators: make videos using music as context, audience, and signal without having to develop an audience first or risk alienation of people you know in real life; as more and more consumers use TikTok, the niches only get deeper and weirder, and the algorithm gets better and better at routing your videos to the right consumers.

- Consumers: get a great feed experience without having to do any work to find and follow accounts; your feed gets better and better as TikTok gets more data about what you like and creators make more videos for every conceivable niche.

This is a strong strategy, but critically, this needs a certain amount of scale to work. When TikTok was much smaller, many of these effects were much weaker. Fewer creators leads to fewer videos to choose from, making TikTok less engaging to consumers. Fewer consumers leads to a smaller potential audience, making it less enticing for creators. How do you solve for this and get to scale quickly, in a landscape as saturated as consumer internet? Paid acquisition. TikTok spent $1b on it throughout 2018 alone, becoming the second-most downloaded app in 2019, topping 2 billion downloads by April 2020, and recently announcing they have 100 million MAUs in the US alone, 50% of those DAUs. This is an enormous amount of money to spend on user acquisition and only makes sense if your ARPU exceeds your CAC (unclear for TikTok) and/or you have strong network effects. With a rumored valuation in the $60 billion range, it seems that bet paid off.

What This Means for Facebook

Instagram Reels isn’t going to supplant TikTok by simply cloning a few of its key aspects. TikTok’s activities require tradeoffs that Instagram might not be ready to make. Pushing Instagram creators to make Reels comes at the cost of other content they could make. Pushing Reels in the Home and Explore feeds siphons off consumer attention that would otherwise go to the rest of Instagram. The resulting signals are much messier given the different and competing goals within Instagram, making it harder to train a great algorithm.

Even if Facebook is ready to eat that cost, the experience is still going to be worse than on TikTok: Instagram’s graph doesn’t overlap heavily with TikTok’s, so Instagram’s ability to leverage their graph to jumpstart Reels is limited. TikTok is successful in part because the content is different than Instagram, where you could make and watch weird, funny, unpolished videos you wouldn’t find elsewhere. This is the critical difference that makes the Snapchat/Instagram stories saga non-comparative: Snapchat and Instagram’s graph had very high overlap, such that people could start using Instagram stories with little loss. This is not true of TikTok/Instagram and makes me skeptical that Reels is going to easily displace TikTok. Network effects are just that powerful.